Can we recreate the baked version of yatsuhashi with different cooking methods?

When visiting Kyoto, there is one souvenir snack that just about everyone brings home to their friends and family: yatsuhashi. It’s a thin, flat sweet made of rice flour and folded over different fillings, though the most typical is red bean paste. There are actually three kinds of yatsuhashi, but the most popular kind you’ll find at most Kyoto souvenir shops is probably nama yatsuhashi, nama meaning “raw,” which is the soft, triangular version that’s similar to a thin mochi.

But did you know that it also comes in a hard-baked form? It’s a dough made from rice flour, sugar, and cinnamon that’s steamed and then baked into a hard rice cracker, and is actually considered the original version of yatsuhashi. We managed to find some to compare to nama yatsuhashi, and they have pretty much the same ingredients; both the hard and soft version from Shogoin Yatsuhashi, a popular brand, had sugar, rice flour, and kinako powder listed, though the hard version also had cinnamon.

▼ Top: the rice cracker-like yatsuhashi. Bottom: the mochi-like nama yatsuhashi.

So in essence, they’re the same product; just one is baked, and the other is not. That got our Japanese-language reporter K. Masami wondering…if she cooked the soft version of yatsuhashi, would it turn out the same as the baked kind you can find in stores? She decided to try it out.

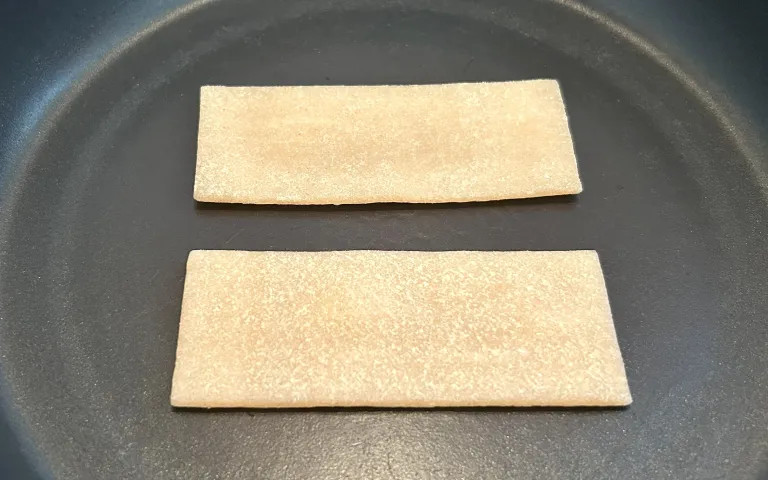

Unfortunately, Masami doesn’t have an oven, so she had to try other methods at her disposal. First, she tried frying them in a pan. She let the pan warm up a bit before putting the soft strips inside. As they made a little crackling noise, the smell of cinnamon filled the room. Perhaps because they’re made with a lot of sugar, they began to brown almost immediately, which made evening out the cooking very difficult.

Masami couldn’t leave them in the pan for long, otherwise they’d burn, so she waited until they looked decently browned and the turned off the heat. After letting them cool, she touched one, but it was strangely still very soft.

It had firmed up a little bit, when she held it on one end, it was still very droopy, and thus had not achieved anywhere near the consistency of a rice cracker.

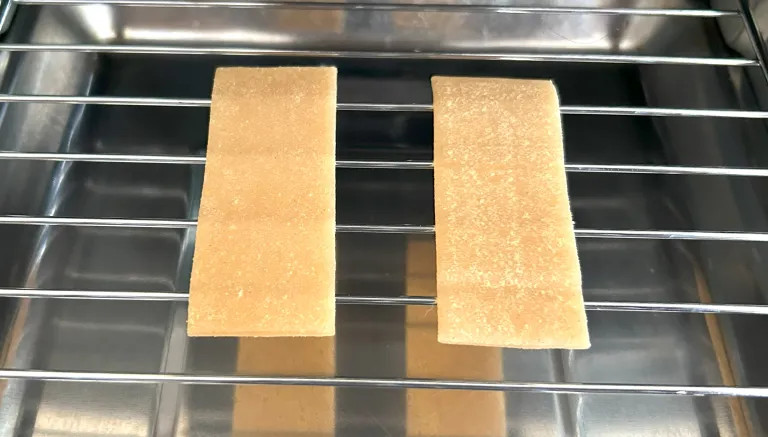

Maybe nama yatsuhashi is destined to stay soft forever? Just in case, Masami decided to try another cooking method: the grill of her gas stove.

Normally reserved for grilling fish, this little drawer is like a tiny broiler that cooks food with an overhead flame. Since it’s a much more direct heat, Masami assumed it would have a different result from cooking in the pan, but it turned out to be just as difficult to moderate the cooking process. Since the heat of the flames is rather strong, the nama yatsuhashi burned immediately even though she had the flame on the lowest setting.

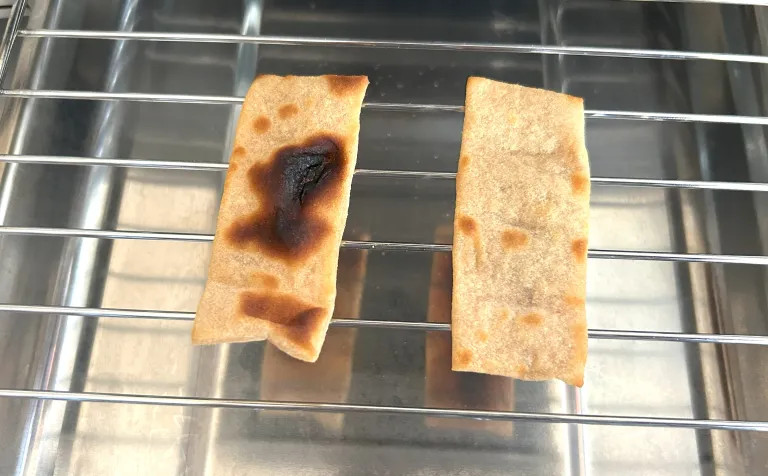

It was a struggle to get them to cook evenly; even a short amount of time caused parts of them to burn. Masami watched carefully and somehow managed to get them to (mostly) brown slightly before quickly pulling them out of the grill.

After allowing them to cool, Masami picked one up and…to her surprise, it was firm! After the debacle that resulted from frying them in the pan, she didn’t think she would be able to firm them up, but somehow she did!

Of course, they hadn’t reached the same level of crispiness as market-produced, firm yatsuhashi. Those are hard as rice crackers, and would break if you dropped them on the floor. But this grilled nama-yatsuhashi was hard enough that she couldn’t twist it like she could with her pan-fried version.

It also had a nice crispy texture, so in Masami’s eyes, it seemed perfect. When she bit into it, however, she realized that, though it was crisp on the outside it was still soft and chewy on the inside, like nama yatsuhashi is supposed to be.

That wasn’t a bad thing. In fact, it was actually really tasty, and cooking it had leveled up its aroma, making it even more flavorful. Masami would recommend it if you’re looking for a different way to eat nama yatsuhashi. If you’re looking for the rice cracker-like, baked yatsuhashi, though, you’ll have to buy it from the store. It doesn’t seem like you can produce the same result by cooking nama yatsuhashi on its own. At least, not with a pan or a grill.

Still, Masami was glad she tried, because it helped her discover not only a new facet of the soft version of the famous Kyoto confectionary, but also that there are a lot more levels to each version of the snack than she initially thought. If you find yourself in Kyoto, definitely pick one or both versions up to give them a try! And if you’re not in Kyoto and suddenly craving some, you can get the same taste from the yatsuhashi gummy candy, which are available around the country.

Images © SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario