They started making korimochi in Nagano a long time ago, but you can still find and try it today.

Freeze-dried food sounds like a recent invention, the sort of thing only made possible and predicated by a combination of the modern era’s high technology and busy lifestyles. But in Japan, they’ve had freeze-dried food for over 600 years in the form of korimochi, or “ice mochi.”

People started making korimochi all the way back in the Kamakura period, (1185-1333). Since they didn’t have electric-powered freezers back in those days, the freezing temperatures had to come from nature itself, and korimochi was developed in the mountains of the Shinshu region, which corresponds to Nagano Prefecture in the Japan of today. Farmers in Shinshu made korimochi by forming thin rice cake sheets, soaking them in water, and cutting them into strips. They’d then hang the strips from the eaves of their homes in the cold alpine winter air for as long as two months, during which the mochi would freeze and dry.

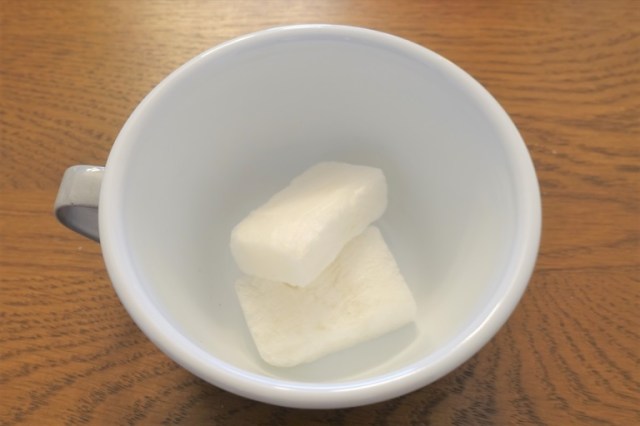

▼ Korimochi

On one of our recent trips through Nagano, we came across packs of korimochi being sold in the Okuwa Michi no Eki roadside souvenir shop in the town of Okuwa. Made by Nagano-based Yamayo Food Industry, the 540-yen (US$4.10) pack contained 12 pieces of ice mochi, and we decided to buy it and try it out.

There is exactly one ingredient in korimochi: mochi rice. Taking a pair of the 4.5-centimeter (1.8-inch) pieces out of the bag for a closer look, they were light and completely dry to the touch, with a finely layered texture.

According to the packaging, there are two ways to eat korimochi. The first is just to eat it as-is, so that was what our reporter Haruka Takagi did for the first part of the taste test.

The texture is crisp, but very different from senbei (Japanese rice crackers). Senbei are grilled or fried, both cooking processes that create air pockets here and there. Korimochi, on the other hand, has a consistently solid feel, similar to another old-school Japanese food, fu (dried wheat gluten). In terms of texture, korimochi couldn’t be farther from the soft and chewy feel of normal mochi.

As Haruka chewed and the korimochi crunched, though, the freeze-dried rice cake began to absorb moisture from her mouth, revealing the same sweet rice flavors beloved by all mochi fans. The disconnect between the flavor and the texture Haruka usually associates with it felt like her brain was momentarily malfunctioning, but once she recovered from the surprise the result was tasty and comforting.

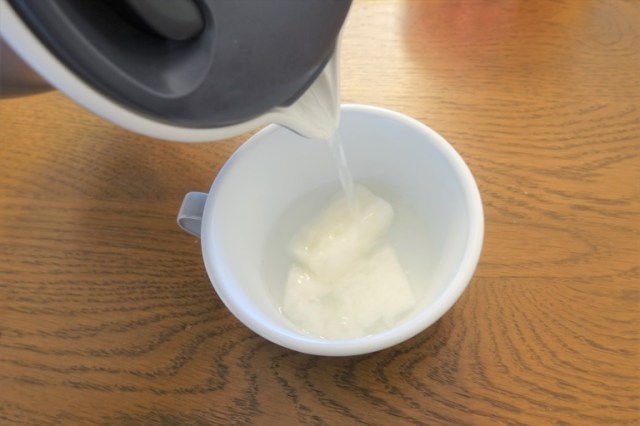

Now it was time to move on to the second way to eat korimochi: mixing it with hot water.

The packaging didn’t say how much water to use, so Haruka tossed two pieces of korimochi in a cup and then poured in enough for them to start floating.

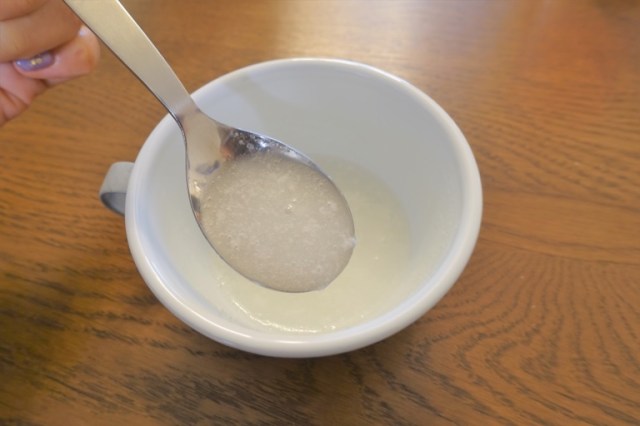

The packaging also recommended adding sugar or honey to make the korimoci into a sweet snack, and so Haruka stirred in a teaspoon and a half of sugar too. After a few more spoon swirls for good measure, the korimochi had dissolved enough to create a creamy cloudy mixture that looked a lot like okayu, Japanese rice porridge.

Again, though, the unique starchy sweetness of mochi shines through in the flavor, giving Haruka a warm and relaxing treat.

She’s also thinking that korimochi would work well with savory twists like ginger or chicken broth, so she’s glad she still has eight pieces left in the pack, even though, since this is one of Japan’s original freeze-dried foods, there’s no need to rush and eat it all right away.

Related: Michi no Eki Okuwa

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario